Archives

Informal writing and research

Route 66 (2020)

During the coronavirus crisis in NYC, touring and gigs have been cancelled, and a good part of my day is taken up with homeschooling (kids age 7 and 10). Our 18 year old is figuring out what it means to graduate high school without every going back to class. Although I was a “good” student, I never much liked the format of the segmented day, switching between subjects and listening to teachers drone on in front of a class. One-on-one with a mentor was (and still is) the way that I like to get information. Also, I got a lot more satisfaction out of using my hands (music, sports, building, art) than doing paperwork.

If I were to design my own curriculum (which is basically what’s happening now), I’d skew towards a non-linear learning method — dive into what’s interesting to you for as long as possible to get deeply into a subject, and don’t worry about the fact that one subject is getting advanced and another is getting neglected — it will even out over time. The most important things are curiosity, focus, and deep engagement. If you don’t dig it, it won’t stick. Harness the natural impulse to explore, rather than forcing everything into an artificial grid. But this isn’t to say that everything can just be freewheeling and creative — some things just have to be memorized and hard-wired through repetition. Spelling is one, and the multiplication tables are another. As a functional person, you don’t have much option but to proficient in these areas. There are a lot of things like this in music as well, repetitive muscular and mental actions that have to be automated so you don’t stumble when inspiration calls. You just have to slog through these fundamentals, and the challenge as a teacher is how to be rigorous without killing the joy of learning.

————————————————————-

Over the years I’ve tried a lot of different ways of teaching the times tables. Since there’s no “fun” way to do it, the best way is probably to get it over with as efficiently as possible. The problem with doing them sequentially (3 x 5 is 15, 3 x 6 is 18, etc.) is that they become a kind of pattern. More like adding and counting than multiplying. Randomization (flash cards) can remedy this. Another problem is redundancy (3 x 5 and 5 x 3, etc.). Double-sided flashcards with inverted versions of the same problem on both sides can fix this. Once you eliminate redundancies (and take out anything with a “1,” which nobody needs to practice), the times tables up to 12 are reduced from 144 to 66 unique combinations. You can easily write these on cards, but I already did it for you. Download and print out the two PDFs below (on thick paper if you have it) and cut off the border of the paper, along the black lines. Glue the two pages back to back so that 2×3 is on the back of 3×2 and so on. If you’re just using regular paper to print, you can sandwich a sheet of construction paper or posterboard between the two sheets when you glue them, to make the cards thicker and more durable. Let the paper dry, and cut it up into cards along the black lines. At home we do the game like this:

1. Warmup round: Kid sits across the table from the parent with the pile of cards. Doesn’t matter which side of the cards are up. Parent starts a timer, and kid picks up the cards one by one and says the answer, tossing it to the parent. Parent checks the answer and throws it back if it is wrong. In the beginning stages, the parent gives some tips and tricks for various ones, whatever comes to mind. The dots on the cards can be used to visualize the concept so it’s not all just abstract numbers. During this round, the parent takes any cards that were answered wrong or took a long time to remember and puts them aside from the rest.

2. Second round: Kid looks through the pile of trouble cards and practices them until they can do them more quickly. They are allowed to start the next round with those cards. Parent starts the timer, goes through all 66 again, starting with the trouble cards. The 2nd round should be a lot shorter than the first one. Usually the kids have had enough at this point.

Here are the levels:

More than 5 minutes: novice (still figuring out how to multiply)

3–5 minutes: egg (rote learning stage)

2–3 minutes: caterpillar (moving slow, but getting there)

1–2 minutes: cocoon (transitional stage, might be in here a while)

Less than a minute: butterfly (done: you are free to fly away!)

I think these can be done at any age range. Currently my 7 year old is a caterpillar, and the 10 year old is in the cocoon. The 18 year old made it to butterfly a while back and graduated. This format is a good start, but maybe you can think of ways to make it more fun with your family. And if you come up with a good way to remember 7 x 8, let me know.

Family video here, PDFs below that:

On Trains and Whales (2018)

MELINDA MAE

Have you heard of tiny Melinda Mae,

Who ate a monstrous whale?

She thought she could,

She said she would,

So she started in right at the tail.

And everyone said, “You’re much too small,”

But that didn’t bother Melinda at all.

She took little bites and she chewed very slow,

Just like a good girl should…

…And in eighty-nine years she ate that whale

Because she said she would!

– Shel Silverstein

Here are some scattered musings on the year 2018, where I was presented with three tests of endurance that showed me a few things about success and failure that I’d like to share. I’m writing this mostly so that I can remember the lessons, but what’s here may also be useful to others. Ok, let’s go. Keeping with the alliteration of Melinda Mae, here’s the form: Monk, Marathon, Mitchell.

I) Monk:

May 30th, 2018 — this was the deadline I set to finish tracking the complete compositions of Thelonious Monk on solo guitar. There were a few practical reasons for it, the kids’ school year coming to an end (after which work time evaporates), increasing construction noise in the neighboring building, and especially the fear of losing momentum. This passage kept coming to mind:

“To keep on going, you have to keep up the rhythm. This is the important thing for long-term projects. Once you set the pace, the rest will follow. The problem is getting the flywheel to spin at a set speed – and to get to that point takes as much concentration and effort as you can manage.”

– Haruki Murakami, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (p. 5)

By mid-winter the flywheel was spinning, but my will was flagging. I was considering a lesson from a previous obsessive project, when I decided I could dash out a book quickly based on some teaching materials (Fundamentals of Guitar) and the process dragged on for three years of cans of worms inside of Pandora’s boxes. Setbacks, excuses, derailments. Thus the deadline for the Monk project, which I saw as a solution to this open-ended problem. Boundaries in a normal recording project are drawn by budget, studio hours, and other musicians’ schedules. Recording at home erases the line in the sand, but watch out for sand in the gears.

Questions that come up in long, solitary projects — Will this ever end? What were you thinking? Have I lost my way? Will this amount to anything? Of course the answer to all of them is the same — don’t worry about it, just go to work. I started recording in September of 2017, working steadily every time that I could get a full day or a few hours free. Once I committed to the project, I knew that the only acceptable approach was a deep dive into the details. Listen to and memorize every note of every tune from original recordings and cross check with available manuscripts in order to have a valid basis for improvisation. Monk’s music is hallowed ground, and while working it out for the guitar I imagined the attention to detail of a translator approaching a sacred text.

What this means is a lot of time sitting in a chair, repeating phrases over and over until a manifestation of the passage reveals itself on the guitar in a fingering pattern or formation. The nine month gestation from September to May remained fixed and immovable in my mind. Here’s the thing — the problem with rigid materials (like concrete or ceramic) is that they are inflexible and break easily. Good for compression, bad for tension. As I sat in the chair for hours, I felt some warning signs — a creeping pain in my back and neck that I dismissed as momentary fatigue. I was unwilling to make an concession to my deadline. I never took breaks for fear of losing momentum. By April I was hitting the wall. I had pain every time I sat down with the guitar, but was putting in longer and longer hours, putting the kids to sleep and going back to practice and record until the early morning. Computer, guitar, computer, guitar. The trapezius system wasn’t built for this kind of repetitive abuse, and was stiffening up, turning to stone.

On May 30 I squeezed the last blood from the rock (“Well You Needn’t”) and knew that I had made a mistake. My back and neck were in continuous pain. I couldn’t sleep, sit in a car or a plane, type, or practice. I went to doctors and physical therapists, who shook heads and wagged fingers. I had finished the project, but my process was unsustainable. My pacing was off, against natural limitations. The deadline wasn’t a bad idea, but the inflexibility of the plan defeated me physically.

Ring finger blowout

Growing up in the Northwest, I remember seeing videos of the 1940 collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which was resonated to death by the wind like a giant guitar string in a feedback loop. Bridges, skyscrapers, and other structures made to exist in the natural world are made to bend a little. Solitary projects require discipline, but discipline in turn requires some accommodation to the curves of reality.

By Monk’s childhood home, Rocky Mount, N.C.

I had taken a trip to Rocky Mount, N.C. earlier in the year to visit Monk’s birthplace, and after seeing the trains running through the neighborhood a recurring theme of the project became the locomotive. The train moves forward with massive momentum, flywheels and inertia carrying the machine forward, arriving on time at the station. I formed the project with idea of the train, but it became more of a whale, refusing to submit to the plan. Melville explains:

“And as the mighty iron Leviathan of the modern railway is so familiarly known in its every pace, that, with watches in their hands, men time his rate as doctors that of a baby’s pulse; and lightly say of it, the up train or the down train will reach such or such a spot, at such or such an hour; even so, almost, there are occasions when these Nantucketers time that other Leviathan of the deep, according to the observed humor of his speed; and say to themselves, so many hours hence this whale will have gone two hundred miles, will have about reached this or that degree of latitude or longitude. But to render this acuteness at all successful in the end, the wind and the sea must be the whaleman’s allies; for of what present avail to the becalmed or windbound mariner is the skill that assures him he is exactly ninety-three leagues and a quarter from his port? Inferable from these statements, are many collateral subtile matters touching the chase of whales.”

– Moby Dick, chapter cxxxiv – The Chase, Second Day

So I chased and caught the whale and kept it in the can for a while. A big can. I had to get Liberty Ellman to clean it up and make it beautiful. I wanted to wait until August, after the drop of Steve Coleman and Five Elements Live at the Village Vanguard, which for me was the culmination of the previous ten years of extreme study. A week later I released the fish into the wild and let it swim away.

II) Marathon:

February 28th, 2018 — this is the day I was accepted by lottery to the New York City marathon. I had only done a small amount of short distance running up to that point and entered on a lark. It’s a stroke of luck to be randomly selected, so I figured I better do it, even though I was already in the weeds with Monk. I would have 8 months to train, which is enough time if you don’t delay.

I’m a believer in persistence over talent. I don’t have much so-called “natural” talent in music, but I’ve been very persistent in trying to improve over the years. And it turns out that you can get a lot done if you just work consistently and don’t wait for some special moment when inspiration is striking (again, the flywheel). I started training regularly but without any particular plan. Just go out every other day and try to go a little farther each week. Ignore the weather or anything else that might give you an excuse, and get to it.

By the time June came around, I had finished the Monk project and found that the back pain dropped off quite a bit once the psychological pressure of my deadline had passed (thanks to John Sarno), but I really wanted to avoid another injury with the marathon training. My problem with the Monk project was lack of a plan, which led to bad pacing and then to burnout. Unlike the Monk project, thousands of people have run marathons according to well tested training methods. So as the Summer started, I decided on one of Hal Higdon‘s programs and followed it to the letter.

In August I got a bad cold and kept powering through the workouts — the same mistake I made with the recording sessions — my times got slower, and I got sicker. Experienced runners know to back off training when they get sick — the result is better if you don’t force the body, even if you fall behind schedule. Still suffering from the Monk injury, I sacrificed a couple of weeks for health. I got back on track, and by the time of the taper (where you recover in preparation for the race) at the end of October, I had run over 700 training miles. My weekly long runs were 22 miles at an 8:45 pace. Ready for white whale #2.

November 4th, Race Day: Unbelievably beautiful weather in New York, exhilarating. The cannon goes off, corral opens, and the crowd starts up the long hill heading east across the Verrazano Bridge. A couple of miles in I look at my watch — 8:15 pace. A fast pace for me, but the running feels effortless. Mile after mile I look down at the watch and it continues to read right around the same time for the splits (8:12, 8:09, 8:07, 8:08, 8:12, etc). I attribute this to my proper training and the two week taper, and the things that I had read about adrenaline giving you an extra boost in the race.

Going out too fast is the most common rookie mistake. I turned the beat around and lost the form. By mile 14 I was having a twinge in my knees from the pounding down the ramp of the 59th street bridge (neglected to train for downhill running). This developed into instability in the quads that I compensated for by trying to back off slowly (splits now at 8:45, 9:06, 9:08, 9:11). But it was too late, and the damage had been done — I hit the wall at mile 23, with sharp pains running up and down the legs and feet, quads turning to jelly. I slowed to an embarrassing slow jog until the finish line. The final time (3 hours, 51 minutes) was objectively fine, but based on my training I was hoping for a more consistent run, and the way that it ended was basically a disappointment.

The thing is, I knew I was doing it while it was happening, but did it anyway. I knew I was exceeding my race pace by at least 20 seconds every mile, and my target heartrate by at least 10 BPM. How was is possible after so much careful training to make such an obvious and avoidable error in pacing? It’s just a matter of experience. Without the necessary reps, it’s easy to confuse euphoria and excitement for relaxation and fitness. The mistake here was different from the Monk project, where I had a great deal of experience in the activity but no plan except for the location of the finish line. In the marathon I had a very good plan and no experience, so I let between irrational exuberance affect my perception of reality. In both cases the problem was pacing. After the race I picked up Alex Whitman’s Endure, which addresses this problem from many angles:

This inescapable importance of pacing is why endurance athletes are obsessed with their splits. As John L. Parker Jr. wrote in his cult running classic, ‘Once a Runner,’ “A runner is a miser, spending the pennies of his energy with great stinginess, constantly wanting to know how much he has spent and how much longer he will be expected to pay. He wants to be broke at precisely the moment he no longer needs his coin.” . . . As I started my second lap, I had to reconcile two conflicting inputs: the intellectual knowledge that I had set off at a recklessly fast pace, and the subjective sense that I felt surprisingly, exhilaratingly good.” (p. 11–12)

With students at the University of Michigan, one of my main subjects is connecting the mind to the body. Sing what you play, play what you sing, clap rhythms to embody them, observe your movements, breath, way of speaking, try to bring your skills on the instrument into the natural realm of gesture and speech. I’ve made a lot of progress in this area over the years in music, and I have a feeling that something from it can be applied to this new pursuit of running, where I’m still a novice and the intellectual and physical aspects haven’t been properly wired together. Training has begun for 2020 with this in mind.

Marathon stages: Anticipation, Fired up, In the groove, Breaking down, Pushing through, At threshold, Relief

III) Mitchell:

March 6th, 2016 — This was the debut of Matt Mitchell’s group “Phalanx Ambassadors” at The Stone in NYC. The gig showed a lot of potential, and Matt eventually decided that he wanted to make a quintet record in December of 2018. Matt is a pianist, about my age, and although I’ve dealt with a lot of situations his music presented some new challenges to me, some that I was genuinely perplexed by. Confession — I’m primarily an ear player. I learned how to sight read fluently when I moved to NYC in 1997 and found out that it was an important skill if I wanted to work, but I still don’t consider working straight off the page to be my strongest area. I trust my ear a lot more than my eyes, so with new material I’ll try to put in enough reps of personal time to get the lines singing along on the unconscious internal loop. That means the pathways have been burned in. A time honored and reliable but time-consuming method, and with Matt’s music there is just an incredible shitload of information. I asked for scores instead of a guitar part so that I could figure out options and see what’s going on, but the music seemed to be an endlessly branching decision tree, where any momentary lapse of concentration would just leave you lost in the wilderness. Anyone who’s seen Matt play can relate how he seems to have trained himself to reach and maintain extreme levels of focus, navigating multiple streams of information that would clog the synapses of two or three competent players. On several of the Phalanx compositions, he’s playing three staves by using his thumbs as a kind of third hand in the middle. Really nuts.

For me to approach this music in an authentic way (that is, not skating), another solitary training period was required in advance of the group rehearsals, working through the seven compositions and finding my way in. I had from the Spring of 2016 to December of 2018 to get to it, and the music sat on my stand for month after month, Leviathan hanging out in the deep waters, waiting for poor Geppetto to sail by and get swallowed. I picked away at sections of it but the approach remained hidden. The summer had begun, which means travel for gigs and family time. Marathon training was in full effect, time slipping away.

26.2 miles seemed like an impossible distance in early 2017, but by the time I was looking at the Matt Mitchell music every day in September, I was already running 6 loops around Prospect park on the weekends. It’s not the distance itself that’s difficult — it’s maintaining discipline over time. Consistency. If you start by running 8 miles a week and increase the mileage by 10% each week (a normal and recommended amount to avoid injury), at the end of four months the weekly total will be about 40 miles. The incremental approach takes away the intimidation factor as long as you allow enough lead time to get the pacing right. One bite at a time, for whatever task. But for any given project, how small should the bites be, and at what speed? In his double edged way, Shel Silverstein got at it with “Melinda Mae” — simultaneously a lesson in persistence and a terrifyingly bad choice of pacing.

I don’t read much fiction any more, but every Summer I seem to circle back to Cormac McCarthy. In the Summer of 2017 I had no time to read, so I was listening to McCarthy while running. The language and imagery of the writing is so dense that you miss a lot of details in the audiobook format. While listening, I’d make mental notes of particular passages that I wanted to go back to and look at on the page. Here’s one. The scene is a father and two young sons looking around in an old cabin for wolf traps and bait:

“There in the dusty light from the one small window on shelves of roughsawed pine stood a collection of fruitjars and bottles with ground glass stoppers and old apothecary jars all bearing antique octagon labels edged in red upon which in Echols’ neat script were listed contents and dates. In the jars dark liquids. Dried viscera. Liver, gall, kidneys. The inward parts of the beast who dreams of man and has so dreamt in running dreams a hundred thousand years and more. Dreams of that malignant lesser god come pale and naked and alien to slaughter all his clan and kin and rout them from their house. A god insatiable whom no ceding could appease nor any measure of blood. The jars stood webbed in dust and the light among them made of the little room with its chemic glass a strange basilica dedicated to a practice as soon to be extinct among the trades of men as the beast to whom it owned its being. Their father took down one of the jars and turned it in his hand and set it back again precisely in its round track of dust.”

– The Crossing (p. 17)

There’s so much here. With little warning the narrative cracks open into a wolf’s-eye vision of the cruelty of humans over the ages, countless generations of slaughter that will be forgotten as the arbitrary needs of men change and move on to the next way to satisfy their appetites. The passage is bookended by “dust,” itself a potent symbol of the inevitable end, things forgotten and decayed (dust to dust). And so on, go as deep as you like.

There’s something about McCarthy’s granular detail that reminds me of Matt Mitchell’s music. You can go in with the microscope, and it holds up under scrutiny and keeps revealing new worlds. I remember an earlier experience of this kind of nested reality about 20 years ago, transcribing a passage from Coltrane’s “Brazilia.” Playing it slowly and uncovering secret information, things that pass by as gestures and shapes on casual listening. Improvised lines with multiple levels of interpretation, spiritual force, melodic integrity, and functional meaning. Massive amounts of information, but nothing unnecessary. McCarthy’s obsessive details are in service to the story. The language isn’t pretentious — it’s functional. If you choose the words with enough intent you don’t need all that punctuation. When I have the book in my hand I tend to go back and read passages over several times. Listening to the book prevents this — you get as much detail as you can and keep moving, follow the through line, trust the narrative. This gave me some ideas for approaching the Matt Mitchell music.

So throughout the Fall I methodically made my way through the pages, keeping up a solid but not excessive pace, programming the muscles, adding distance, increasing threshold. Eating whale. After November 4th (marathon day), I went in deeper, looking at the miniature episodes that appear in looped sections and phrases, internalizing, polishing, finding the through line that sings. By December’s group rehearsals it was clear that everyone else had done some version of this — a very prepared band. The only thing to do was to assemble, file off the rough edges, wind it up and let it loose. Two days in the studio and the project was in the can — two of the hardest compositions were first takes. The details were in place because of preparation, and the focus was on the energy and vibe. Studio pacing is a delicate balance of technical and psychological factors, and Matt had producer David Torn on hand, a master train conductor.

In the marathon there are runners called “pacers,” who hold up a sign with a desired finishing time. If you want, you can run with the pace group and alleviate the responsibility of monitoring your own time. Actually, the pacers run slightly ahead of the target time, so that if people lag behind at the end they may still hit the mark. The psychological advantage of knowing that someone is setting the pace is significant. Fewer distractions, better focus. With a solid producer in the studio, you can just concentrate on performing and executing. Torn’s method is to be invisible but functional. You might say, a Freddie Green approach. And with such difficult music, I would say that a producer/pacer is essential.

A Matt Mitchell tune

Questions: What is the benefit of an extreme approach — couldn’t things be less punishing? Don’t you just want to play, and do your thing? Don’t you just want to enjoy yourself? Not really. The impulse is more to explore and expand, which is different than fun and enjoyment. In this case, Matt gave the band a very clear idea of what was involved, what kind of challenge it would be to nail the music, and set the pace precisely. Leaders will attract like minded collaborators through the audacity of their plans and ideas. To take an extreme example, Ernest Shackleton didn’t have much trouble enlisting the crew on his quest to cross the Antarctic continent:

“When Shackleton announced his plans he was deluged by more than five thousand applications from persons who asked to go along. Almost without exception, these volunteers were motivated solely by the spirit of adventure, for the salaries offered were little more than token payments for the services expected.”

– Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage (p. 18)

Shackleton’s mission failed, but is remembered as an incredible tale of endurance. The thing about physical territory is that it runs out. With music, you can just keep building more territory and expanding into it, as far as the spirit of adventure leads. If the music presents the opportunity to expand, other people will probably get involved — as Monk said about his compositions: “Those pieces were written so as to have something to play, and to get cats interested enough to come to a rehearsal.” Still a good strategy.

So as more birthdays pass (I’m at half a piano now), there’s little room for delay or compromises. Projects are more challenging, and time is harder to come by. Cormac McCarthy, tongue in cheek (but maybe not), says, “Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.” Talk about extreme. I prefer David Torn’s response during the Mitchell session when I marveled about his knowledge of some piece of audio gear: “Is there any other way to be in than deep in?”

D.C.:

Deep in. In the territory of the imagination and human nature, the most fearless explorer that I can think of is Toni Morrison. I think it’s important when talking about endurance to think about the difference between these tests we choose to take individually (marathons, children, etc), and the tests brought about by the unintended circumstances of life on individuals and communities, the “push to the abyss”:

“I think my goal is to see really and truly of what these people are made, and I put them in situations of great duress and pain, you know, I ‘call their hand.’ And, then when I see them in life threatening circumstances or see their hands called, then I know who they are. And some of the situations are grotesque. These are not your normal everyday lives. They are not my normal everyday life, probably not many peoples’. It’s not that I deny that part of life in life. It just doesn’t produce anything for me. If I see a person on his way to work everyday doing what he is supposed to do — taking care of his children, then I know that. But what if something really terrible happens, can you still — so that it is always a push towards the abyss somewhere to see what is remarkable, because that’s the way I find out what is heroic. That’s the way I find out why such people survive, who went under, who didn’t, what the civilization was, because quiet as it’s kept much of our business, our existence here, has been grotesque. It really has. The fact that we are a stable people making an enormous contribution in whatever way to the society is remarkable because all you have to do is scratch the surface, I don’t mean as individuals but as a race, and there is something quite astonishing there and that’s what peaks my curiosity. I do not write books about everyday people. They really are extraordinary whether it’s wicked or stupid or wonderful or what have you.”

– Conversations with Toni Morrison, (p. 180–181)

Morrison’s characters are forced into the boundaries, the margins of society, the thresholds of human endurance. Through their grotesque suffering they show us what is possible. The boundary is where the trickster lives, turning the rules upside down, revealing hypocrisy and telling truths. A bluff only works if nobody calls your hand. Musicians search for the boundaries of their abilities because that’s where breakthroughs happen. Performing under extreme conditions filters out the extraneous and the mundane. The fact that Thelonious Monk created his body of work, given the circumstances of his life and time, is a miracle of human creativity, focus, and imagination. Studying and learning this body of work is none of these things — it’s a personal challenge, an interpretation of the existing canon. Some publications have remarked on the “devotional” quality of my recording of Monk’s music, which I think is an accurate word. Playing Monk’s music is serious business – don’t disrespect it, please. Think about what that music represents for so many people and that fact that nothing like it will ever be made again.

al Coda:

Recently there was an article in the New York Times about ultramarathoner Courtney Dauwalter, titled “The Woman Who Outruns the Men, 200 Miles at a Time.” It included this quote from biologist Heather Heyeng:

“This is about stamina, and stamina is some combination of yes, strength, but also psychological will. It begs the question, is there something going on for women perhaps given our very long evolutionary history as mammals who spent a long time gestating and then giving birth, that gives us a psychological edge in extremely long-term endurance events?”

I certainly don’t doubt it, based on personal experience. Whatever your bet, your hand will be called by childbirth and found wanting. And in terms of taking the long view on things, the women in my life have certainly been the ones to show the best judgement. My running mentor is Ellen Rowe, a celebrated professor at the University of Michigan and ultramarathon trail runner. The last time I saw her she had just completed a 100K in California. While struggling with pacing, I asked for some rules of thumb — she says: “start slow, then go slower.” Advice for a person who tends to lose patience. Although Ellen posts excellent finishing times, her goal isn’t purely speed. At the most extreme distances, over unfamiliar terrain and unpredictable weather, the main goal is to finish. Starting slow doesn’t mean actually running a bad pace, it just means run slower than you think you can, because your perception of what pace you can maintain is probably inflated. While listening to a podcast, I found out about a new book by the champion runner Deena Kastor that focuses on the power of the mind. Here’s a relevant passage:

“I noticed my coach kept emphasizing good attitude. At first, I thought this meant being upbeat. Eventually, thought, I realized a good attitude went far beyond the general idea of staying positive. It was part of a discipline, a long-cultivated habit of building and sustaining a positive mind capable of turning every experience into fuel.”

– Deena Kastor, Let Your Mind Run (prologue)

Kastor distinguishes between the clichés of positive thinking and the discipline of “emotional control” — “let your mind dictate your pace, not your emotions.” As an elite athlete, Kastor is able to concretely measure the effects of different psychological approaches in minutes and seconds. In order to get consistent results, she needs to find reliable ways to enter a place in the mind and stay there as long as necessary.

Being somewhat impatient, this kind of steady, long term mental discipline isn’t naturally my process. I’ll go deep for a while down in the whale’s belly, then come up for air, and so on. More of a roller coaster than Metro North. I can reach emotional states in performance that I find impossible to remember later on. I’ll work out concepts in practice that become impossible to access in the heat of the moment on stage. This means, work on control. The primary goal is to be able to pick up the instrument and play exactly the sound that comes to mind, every time, regardless of how your day went, who’s in the audience, etc. This doesn’t happen through magical positive thinking — it’s incremental training, at a snail’s pace.

New Year is here, goal setting time, and I’ll make a few for 2019. 2018 taught me that I need to work on pacing, and be careful about how many trains are on the tracks. I’ll aim for a few reasonable targets and see about setting the right tempo. Resolutions often don’t amount to much, because they are momentary aspirations (“I think I can”). A higher goal is Kastor’s permanent “positive mind,” or Murakami’s reliably spinning flywheel (“I know I can”). And yes, this brings us to the inevitable Shel Silverstein ending:

THE LITTLE BLUE ENGINE

The little blue engine looked up at the hill.

His light was weak, his whistle was shrill.

He was tired and small, and the hill was tall,

And his face blushed red as he softly said,

“I think I can, I think I can, I think I can.”

So he started up with a chug and a strain,

And he puffed and pulled with might and main.

And slowly he climbed, a foot at a time,

And his engine coughed as he whispered soft,

“I think I can, I think I can, I think I can.”

With a squeak and a creak and a toot and a sigh,

With an extra hope and an extra try,

He would not stop — now he neared the top —

And strong and proud he cried out loud,

“I think I can, I think I can, I think I can!”

He was almost there, when — CRASH! SMASH! BASH!

He slid down and mashed into engine hash

On the rocks below… which goes to show

If the track is tough and the hill is rough,

THINKING you can just ain’t enough!

– Brooklyn, Dec 30, 2018

19 minutes with JSB (2017)

I’m not a trained classical guitarist, but since childhood I’ve loved messing around with Bach. I play material in whatever way feels right, without worrying about stylistic matters. The Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major (BWV 1005) has been a part of my life for 15 years or so. I find that playing through all four movements puts my mind and body in order, and is also an inexhaustible lesson in composition. The hypnotic mutations of the Adagio lead directly to the Fugue, the centerpiece which is the longest fugue written by Bach for any instrument. The largo is made for slow lengthy strokes of the bow, so it seems like a good challenge to try to get some lyricism going with the pick. The Allegro Assai is a joyful melody but a brutal picking workout, especially when adding accents that move across the figures. Specifically, some of the things I focus on while playing this piece are:

Adagio (Classical Guitar, fingers): vibration, sonority, dynamics, breath, waves, mutation.

Fugue (Classical Guitar, fingers): melody, counterpoint, independence, balance, cadence, gesture, momentum, drama, storytelling.

Largo (Electric Guitar, pick): delicacy, touch, clarity, silence, vulnerability, melodic contour and continuity.

Allegro Assai (Electric Guitar, pick): picking gymnastics, skips and leaps, articulation, accents, rhythmic precision, velocity, fluidity.

As an an additional challenge, on this recording all movements are played at 40 beats per minute, with these relationships:

Adagio: quarter note = 40

Fugue: one bar of 4/4 = 40

Largo: eighth note = 40

Allegro Assai: one bar of 12/8 = 40

This clocks in at 19 minutes and 19 seconds, with the first two movements at fairly normal speeds, the third very slow, and the fourth very fast. When played in this way, I’ve found that the Sonata has a few lessons about rhythm as well (especially the last movement, which is played here in a triplet feel).

Recorded using Gibson 1963 CO Classical and 1978 ES175 CC guitars, a stereo pair of Rode NT5 microphones, and a Fender Twin Reverb amplifier, June 2017.

Charlie Christian at 100 (CC@C) (2016)

Charlie Christian is the greatest guitarist who ever lived. That’s my opinion, but many would agree. He pioneered the approach on guitar that I strive toward, which has to do with rhythm and feel. It’s possible to play many notes at the same time on the guitar, but it’s not a piano, and it never will be. Charlie Christian showed us some things about rhythm on this instrument that people still haven’t dealt with.

I studied with Rodney Jones for many years, who studied with Barney Kessel, who spent a little time with Charlie Christian. From this I can claim a very tenuous connection to the CC lineage. I play a Charlie Christian Guitar, but it’s not about the gear — it’s about that feel. All the fancy notes in the world won’t mean anything without a strong beat.

Here’s an article I wrote for Ethan Iverson’s “Do The Math” about the “Stompin’ at the Savoy” solo. There’s a video of me playing the solo along with the record, analysis, and some opinions and speculations.

Charlie Christian will be 100 this July 29. We remember him by keeping it moving, keeping that rhythm.

– Miles Okazaki, 2016

Won’t you lead me there? (2015)

Some thoughts on shapes:

A great master Ornette Coleman died today. When I was about 14, I heard a saxophone and trumpet playing a melody on the car radio. I didn’t stay around for the DJ’s announcement, and the melody stuck in my head. It kept coming back randomly in my mind for years — I could sing the whole thing, having only heard it one time. I remembered the shape of it. It was driving my a little crazy — I didn’t know anybody who could solve the riddle. When I was about 20, I picked up a copy of Ornette’s Something Else!!! and there it was, “When Will the Blues Leave.” The shape was what stuck with me, the contour of the melody, the break for the drums, the leaping at the beginning contrasted with the snakiness of the ending. This was an early composition, but those shapes! So many of the compositions could be identified by the shape of the melody alone — “Peace,” “Round Trip,” “Law Years,” “WRU.”

Recently I heard a rehearsal tape where Ornette is working with Ed Blackwell, describing what he wants from the drums. The focus is on something like, trying to get somewhere without sounding like you’re trying to get somewhere. A couple of quotes:

“What I’m saying is that, when you were doing it then it was just like saying, you were playing a certain rhythm that you know you have to play because the next thing that’s coming up is going to justify what you just done. But cut that all loose.”

“The only thing I’m trying to get clear is that isn’t there a certain method that, the way you play ideas on the rhythm, is you can set it up to where it gives you a feeling that you’re going — like anybody listening would get a feeling like there’s something you’re going to get to? . . . What I’m saying, that is what’s the difference between you having to adjust your idea to sounding like we’re going somewhere than playing actually what’s right there. What you actually play, without making it sound like it’s going somewhere.“

Rest in peace, Mr. Coleman, and thank you for leading us to so many places.

In my own practice, I’m working on some kind of “shape theory,” and recently taking another look at Allen Forte’s The Structure of Atonal Music, which has been on my shelf for about 15 years, cracked open and put away many times for lack of patience. Too much nomenclature that I don’t understand. And this book is from 1973, so I’m way behind. I wish that I could read what modern music theorists are up to because there are so many useful ideas, but I don’t have training in this area, and have always been turned off heavy jargon. So I end up going through things very slowly and translating them to more plain language. I admire the rigor of Forte’s book, but stuff like this is impenetrable to your average practicing musician (p. 7–8):

If we let A be [0,1,2] and t = 1, the process by which B is produced can be displayed as follows:

T

t = 1

A B

0 → 1

1 → 2

2 → 3

Observe that every element of A corresponds to an element of B and that the correspondence is unique in each case — that is, some element in B does not correspond to two elements in A. Thus, transposition can be regarded as a rule of correspondence — namely, addition modulo 12 — that assigns to every element of B exactly one element derived from A. We will borrow a conventional mathematical term to describe such a process and say that A is “mapped” onto B by the rule T. The notion of a mapping is more than a convenience in describing relations between pc sets. It permits the development of economical and precise descriptions which could not be obtained using conventional musical terms.

Translation: “Take the intervals of your material and play them “down” instead of “up” (or vice versa). For example the intervals in the melody [C,E,G] (up major third, up minor third) played down instead of up from C makes [C,Ab,F] (down major third, down minor third). The word that I don’t really get in the quote is “equivalent” — the system here makes no distinction between sounds that are intervallic mirror images. For example, there is no way to distinguish between a major and minor triad, which are structural inverses (both called “3-11″ in the list of sets, Appendix 1, p. 179). But musicians know that these are two different sonic realities. Personally, I can’t hear a minor triad as a “downward” major triad. I hear a sound that has a root, a 5th, and a pitch a minor third above the root. This doesn’t mean it’s not interesting to think about. In fact, I’m pretty obsessed with ideas about mirrors and symmetry. Steve Coleman has developed whole worlds of music based on this idea. But my ear tells me that the root of [F,Ab,C] is F. Structurally, it’s related to [C,E,G], but the sonic impression is distinct.

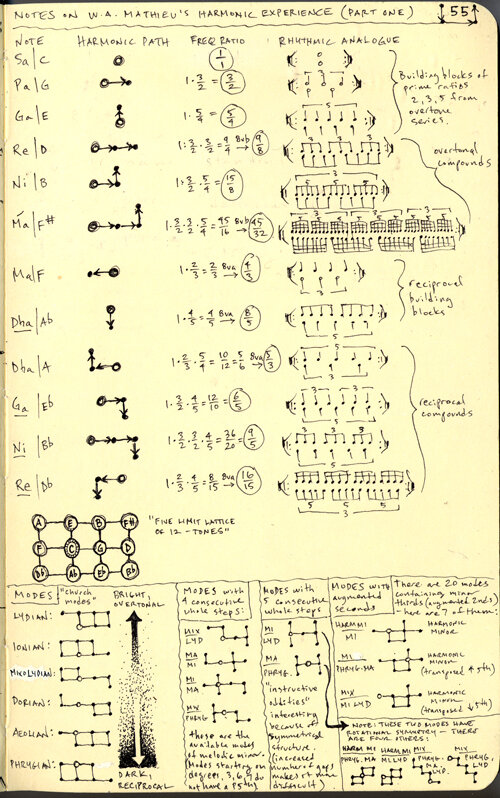

So Forte lists 12 trichords in his Appendix I. Trichords are structures with three notes. Usually, they are listed in some kind of “prime form,” or the inversion that has the smallest range. Kind of like “root position” for a common triad. Other people that I’ve seen also list 12 trichord types (John Rahn, Elliott Carter). I wonder what Schillinger’s version is — I’ve never been able to justify the cost of those giant books. I’m sure there are many, many versions of this, because it’s pretty easy to figure out. John O’Gallagher hipped me Peter Schat’s “Tone Clock,” which has to do with layering trichord shapes to partition the 12 tones.

O’Gallagher’s Twelve-Tone Improvisation is the book that is the most convincing study for me in this area. Rather than a list of numbers, he describes the 12 trichords intervallically, which is much more intuitive for improvising musicians. For example, Forte’s 3-3, with Pitch Class Set [0,1,4] could be thought of as [C,C#,E], or any of its 12 transpositions. But this set can also go “downward” (inversion), which would be [0,11,8], (each “mapped” pair has to add up to 12), or [C,B,Ab] and its 12 transpositions. Lots of calculating. Lots of focus on fixed pitches as opposed to structural content. O’Gallagher describes this structure with the more user-friendly “1 + 3″ or “3 + 1.” This would give you (starting on C): [C,C#,E] or [C,D#,E]. The intervals are shuffled within the same frame. You see right away what the content is. It may seem a trivial distinction, but this intervallic description relates much better to the way things move and connect. Of course, maybe it’s just a better tool for the job — Forte’s book is, I guess, more about analysis than composition or improvisation. I believe that John (having hung out and played with him) has effectively trained himself to hear these asymmetrical trichords (of which there are 7) as two sides of the same coin. Major and Minor triads are like two children from the same family. Or maybe twins, male and female.

Anyway, I’ve meditated on these 12 trichords for several years now, and decided that I hear 19 sounds. This is because 5 of the trichords are symmetrical (containing at least two of the same intervals) and their structure doesn’t change upon reflection. They may sound transposed, but the quality is the same. For example, reflect the diminished triad [C,Eb,Gb] around C to get [Gb,A,C] — same structure, transposed by a tritone. It has two identical intervals (a minor 3rd). The other 7 trichords in Forte’s list are asymmetrical (containing 3 different intervals), and sound structurally different when reflected. This makes 14 asymmetrical + 5 symmetrical, or 19.

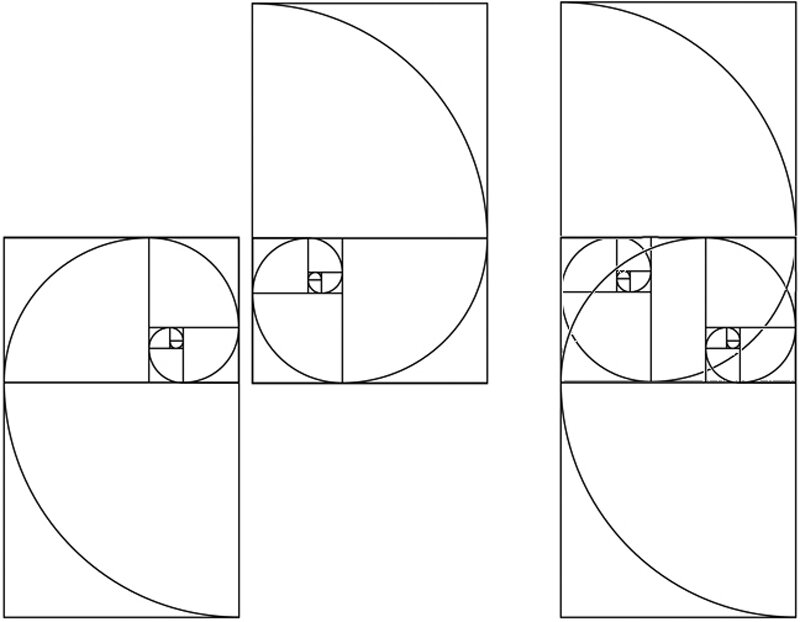

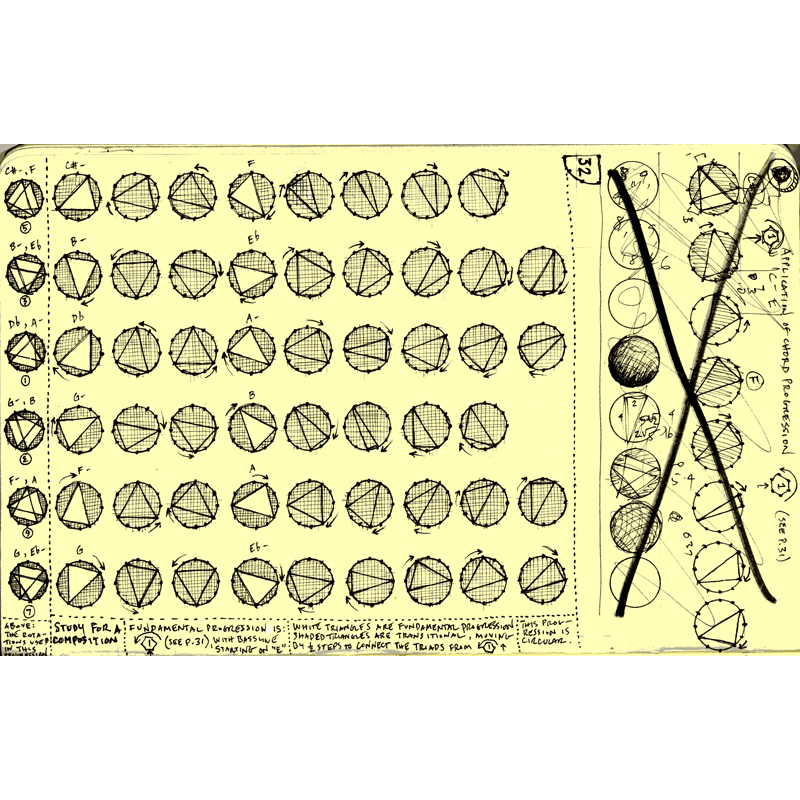

I have a little trouble mentally with lists of numbers — for example in integer notation, [0,4,7] [0,3,8] and [0,5,9] are all major triads (Cma, Abma, and Fma). But this isn’t very apparent to me by just looking at the numbers. I know that these type of things are very far from what’s in my mind while improvising. Much easier for me is to draw the shape on a pitch circle and see what it looks like. The three sets above then look like this (imagine “C” at the 12:00 position, and read clockwise).

It’s pretty easy to see that these are all rotations of the same shape. It took me a little while to get used to this notation, but after a some time it allowed me to see relationships and patterns very quickly, closer to the fluid way of thinking (or not thinking) while improvising. I’ve always liked the idea of visualization as a tool, but the idea of shapes conveying data efficiently was really kicked into high gear after taking a look at Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information.”

Thinking about intuitive interfaces, consider the idea of the “Interval Vector” of a pitch set (another concept in Forte’s book). All this means is “how many of each type of interval there are” in a given set of pitches. The text goes through some pretty tortuous calculations to get all of the numbers (looking at the differences between each pair of numbers, etc, p. 14–15). Basically, it’s the problem of when you walk into a room and everybody has to shake everybody else’s hand. During the greeting, you figure out the difference in your ages (subtract 12 if this number larger than 11). Then count how many of each number you get for all possible handshakes. Long process, likely to make a mistake. On the circle, it’s pretty easy to look at the shape and see the intervals quickly and accurately. For the major triads above, just go around and look at each pitch: How many semitones follow any of the three pitches? None. How many whole tones? None. How many minor thirds? One. How many major thirds? One. How many Perfect fourths? One. How many tritones? None. You don’t need to go farther than this (the number of perfect 5ths is the same as perfect 4ths, and so on). This gives the interval vector (001110). The interval vector thing reminded me right away of some things that been explained to me about devices used by Henry Threadgill where the interval content of a set of pitches is treated as a set of improvisational possibilities.

So anyway, I decided after some study that to my ear I’m on the 19 trichords side of the fence, or triads, or whatever you want to call them. Three notes that you think of as being a musical “word.” Let’s try to crack the code — How are they all related to one another? Well, a useful way to meditate on information is on a mandala. Here’s one, with only one rule: All trichords that are connected by a line have to be only slightly different — you can move from one to another by moving one of the pitches by one semitone:

Any three pitches you name will be one of these 19 shapes. This particular array (or some tangled version of it with the same connections) is the only possible way to organize the shapes under this rule of close relationships. The numbers here give the old fashioned integer notation, starting from the white circle and reading clockwise. The center pitch of each triad is at 12:00, to see the shapes in a similar orientation. The dotted lines connect triads that are almost the same. They only differ by one pitch moving one semitone. For example, you can see that the minor triad (0,3,7) and the major triad (0,4,7) are connected by a dotted line. The difference between these two is the semitone movement of the 3rd, minor or major. The pathways along the dotted lines are possible “mutations” within the larger triad organism. The five symmetrical triads are the spine, and the assymetrical triads form the wings. At the head is triad (0,2,7), which has a special significance for those who study the music of John Coltrane — for example, the opening of “A Love Supreme,” (B,E,F#,B) which is (0,2,7) where E = 0.

I’ve made some other mandalas of these 19 shapes. It’s a way of getting the mind around a certain amount of information. See how much is actually there without getting overwhelmed. Find an analogy somewhere in nature maybe, to attach some symbolism to the data. For example, there is a progression of the moon phases called the “Metonic Cycle” that takes 19 years to complete. After 19 years, the moon will be at (very nearly) the same phase at the same time of year (this was one of the cycles measured by the ancient Greek “Antikythera Mechanism”). You could take any date and see what the moon phase is over the course of this cycle, associate each phase with a triad, and come up with a complete progression of the 19 triads. An idea of using one shape to get at an understanding of another.

So after some study here, the next question is, let’s get past 3 notes — what do all possible pitch shapes look like? Is there a way to organize them in a way that is maximally useful for improvisors?

Well, first of all, how many are there? Forte lists 220 pitch sets in appendix 1 (for some reason not including sets of 1,2,10,11, or 12 pitches, which I also don’t understand, since these are things that we use quite a bit). So, if you are on the 19 triad side of things (rejecting the notion of sonic equivalency in inversion), you come up with 351 pitch sets. That is, all possible pitch shapes between 1–12 notes in 12 tone equal temperament. This is a lot of information, but doing some “humanizing” of the data can be a way in. Take the number 351. This divides up certain ways. For example, you could take it in smaller pieces, 13 groups of 27. This sounds almost like a calendar. Imagine a world where each pitch shape is a day, there are 9 days in a week, and 3 weeks in a 27 day month. There are 13 months, and if you put a vacation day in between each one, plus an extra on January 1 (for the hangover), you get (13 x 27) + 14, or a 365 day year. Map your regular calendar onto this one. Take a year and go through all possible shapes, and you must learn something.

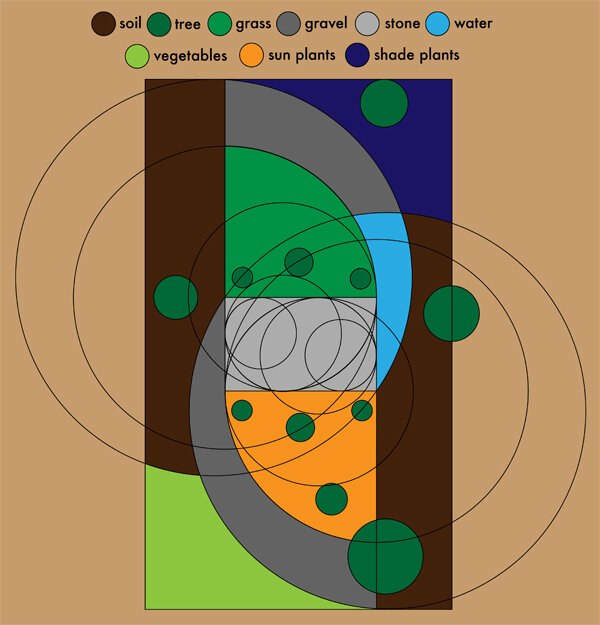

So I figured I should do that. It’s a way of using one familiar, ingrained system (the calendar) to get into a less familiar bunch of information (“learn a word a day” type of thing). I mean, it’s just these 12 pitches, shouldn’t we know the materials of our trade inside and out? The main question is, how to order the shapes? Forte’s ordering is based on the “Cardinal Number” of each set (how many notes in the shape), and an ordering within each cardinality based on an permutative algorithm that finds smallest intervals. On the surface, this ordering looked tedious to me for practice purposes. It would be good to change it up a bit more. What if the order could somehow imitate the seasons, one big cycle? This would logically start with a single pitch and end with the chromatic scale. Those define a minimum and maximum range of pitches. So then you could just go through visually and arrange the shapes by the range that they cover, which is very useful musically. Then the whole cycle is like a slow filling in of the chromatic scale. The pitch sets get appropriately full as the cold winter months march on. The 13 months of the tonal calendar with 14 empty days could look like this:

Recently I started doing a daily study of each of these pitch shapes, following this order, one per day. I’m about two weeks in. June 18th is the next day off. Right now is the time of year to deal with shapes that span 8 semitones. There’s a bit of a Thelonious Monk theme going on. June 10th was (0,3,5,6,8) or [C,Eb,F,Gb,Ab], which you hear at the beginning of the melody of “Little Rootie Tootie” (Ab,Eb,C,Gb,F) and also at the beginning of “Bolivar Blues” (transposed to Bb). June 11th was (0,3,5,7,8) or [C,Eb,F,G,Ab], which you hear (transposed up a major 3rd) at the beginning of “Monk’s Dream” (C,E,G,A,B). But maybe this is changing, because tomorrow (June 12th) is (0,3,6,7,8), or [C,Eb,Gb,G,Ab], which goes along with the final lyric of Hoagy Carmichael’s “Skylark”: “Won’t you lead me there?”

– Brooklyn, 11 June 2015

Chicago Guitar (2015)

I’ve been living in Chicago for nearly a month, staying in Hyde Park with Steve Coleman’s band during a residency on the South Side. We’ve been doing concerts almost every night, workshops during the day, and hanging. It’s been some long hours in the shed, but I’ve been trying to find some time to venture out and explore the great variety of guitar players in this town. Here’s some thoughts on four generations of Chicago guitarists.

With Mike Allemana, Logan Center

I met Mike Allemana about 8 years ago through Steve Coleman while doing a project in Michigan. I had heard Mike’s name a lot because he was Von Freeman’s guitarist at the time. He ended up working with Von for 15 years — some serious experience. Mike is a historian of the Chicago scene — he drove me around and showed me where all the old clubs used to be, relating stories about Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, Julian Priester, Eddie Harris, and other Chicago legends. Mike can handle the L-5 — an unflappable, soulful and mature player, having come up with veteran players, internalizing the history of the city.

At George Freeman’s house

A living piece of history is Von Freeman’s brother, George Freeman (born 1927). Mike took me to George’s house three times, and we sat and played and listened to stories for hours. These included getting turned on to guitar from Bo Diddley, hanging with John Coltrane in the late ‘40s, and playing with Charlie Parker in the early ‘50s. George grew up with the sound of the saxophone (coming out of the closet, where Von practiced), and his approach to the guitar seems to emulate horn-like slippery gestures and phrases. His setup is the most bizarre I’ve ever seen — an old 335 with frets filed flat, strings of strange gauges, a homemade pick, a strap drilled into the bottom of the body.

George launched into tune after tune without hesitation. We played well worn stuff (Stompin’ at the Savoy, Indiana, Sunny Side of the Street, Lover, Cherokee, etc) and some things that I didn’t know so well (The Second Time Around, Fine and Dandy, some originals). George is a kind of trickster, often taking left turns on purpose — “those wrong notes come in handy” he said a few times. Most of our talk was about “bebop guitar,” but he kept threatening to “turn on the grease knob.” He did that on our last visit, cranking up and bending strings, playing a dirty blues.

With Henry Johnson

I heard about Henry Johnson (born 1954) years ago from my teacher Rodney Jones, who is about the same age. Then Steve Coleman (who is also the same generation) kept telling me I should look him up. So I called him and asked if I could come by his place and hang out. He generously spent the better part of a day with me, talking shop, playing, and telling stories. Henry is a link to a specific tradition of guitar playing in the Charlie Christian / Wes Montgomery / George Benson lineage. He has a serious résumé (Jack McDuff, Dizzy Gillespie, Stanley Turrentine, Jimmy Smith, Ramsey Lewis, many others), and plays with a light touch, relaxed and in the pocket.

We talked a lot about Benson, who is his mentor and who I have a lot of questions about. My picking style is modeled on Benson with some science fiction thrown in, and I wanted to ask Henry for some right hand secrets — “you’re doing it already, just lighten up a little and you’ll be good,” he advised. I’ve been working on that for a long time — the light touch is key to so many things (speed, relaxation, etc). I have to balance this with my own aesthetic of heavily accented, rhythmic playing. We talked about gear (specifically, Thomastik 13s and heavy picks), 3-fingered playing, tunes, and how there aren’t many young guitarists carrying on in the line of plug and play — clean tone, dealing with the naked instrument and what you can do with it. Henry came down to a Five Elements gig and sat in. The band played “Recordame” and “All the Things You Are” in some different rhythmic cycles and Henry swam through it like a fish in the water.

With Bobby Broom

I had been hearing about Bobby Broom (born 1961) for many years, but I neglected to check him out until he came out with a record of Monk tunes in 2009.

After I heard his time feel on this record, I was a fan. He’s a rare guitarist with a relaxed sense of rhythm and a conversational approach to phrasing, combined with a heavy sense of the groove and the blues. A restrained player who can whip some ass if necessary. Bobby has a long list of credits, most notably as the guitarist for Sonny Rollins. Lately, his band has been touring with Steely Dan.

I came to meet him a couple of times at Andy’s, where he was playing in the house band. We sat talking and watching the jam session. A lot of notes flying around. Bobby showed noticeable relief when the air cleared out for a bass solo. You can tell from his playing that he values space. His patience in the process of improvisation holds your attention — there’s suspense involved, and storytelling. New York tends to be a more “in your face” vibe, so for me this kind of approach is like fresh air.

With Scott Hesse

I met Scott Hesse around 1997, when he was an ex-student of Rodney Jones, and I was just arriving in New York. We had some marathon guitar nerd sessions with Rodney, trading choruses of rhythm changes or Giant Steps for hours and that kind of thing. Rodney taught (and still teaches) a skill set that is very versatile. Focus on time, groove, picking, accuracy, fundamental stuff. Some of his students went on to commercial or pop music routes (most notably Lukasz Gottwald a.k.a. “Dr. Luke”) and some took more esoteric routes (Scott and yours truly).

Scott is a phenomenally talented player — his fundamentals are rock solid. Tone, articulation, repertoire, time. He moved to Chicago in 2004 and found like-minded folks at the Velvet Lounge, where he spent a lot of time working with Fred Anderson and musicians associated with the AACM. When I called him, he was in the middle of moving his family to a new house and getting ready for a recording session the next day, but he made time to hang for the night and catch up. (By the way, this place has an incredible burger.) Being about the same age as me (Scott’s from ’70, I’m from ’74), we talked a lot about choices that we’ve made, and where we’ve arrived so far. “I don’t get called much for straight-ahead gigs any more, but I’m doing almost entirely stuff that I want to do,” he said. It’s a big accomplishment in our field, to find a unique direction, follow it, and still manage to stay afloat.

With Steve Coleman

Tomorrow I’ll play in Millennium Park with Steve Coleman, finishing up this Chicago adventure. I’ll be thinking about what I’ve gathered from these practitioners of the guitar. As musicians we deal with a lot of areas — theory, composition, repertoire, business and logistics, etc. Sometimes I get so involved in this stuff that I neglect research into the instrument itself. There’s no end to improving your craft — sharpening the tools and seeing what other people are doing. The age of the internet hasn’t been able to defeat the geography of the music scene.

There is no substitute for physically going somewhere and getting into it — like all places with a deep history, Chicago has a specific vibe. I’ve tried to catch a piece of it. Thanks for the hang, folks, see you next time.

– Aug 5, 2015

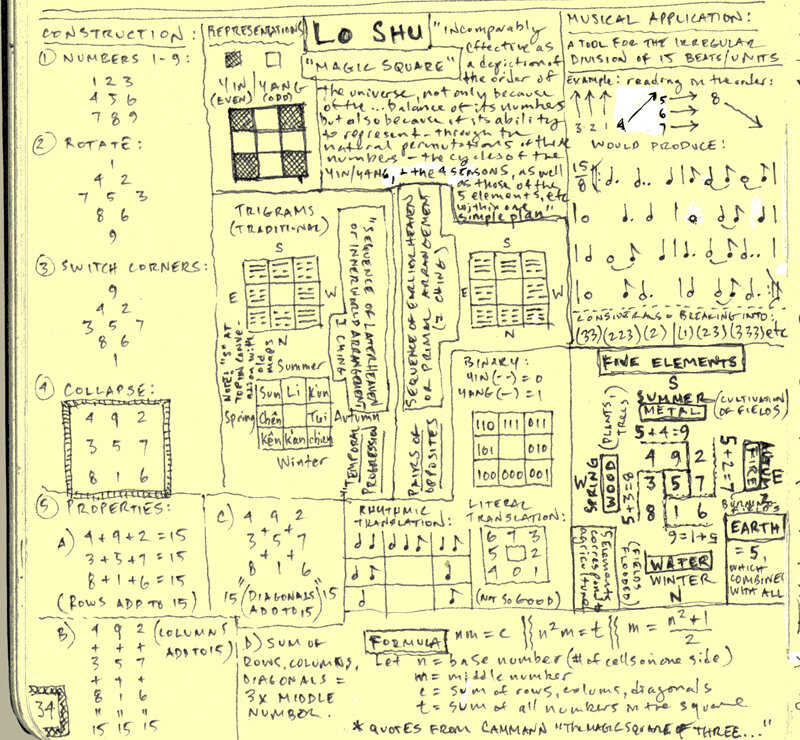

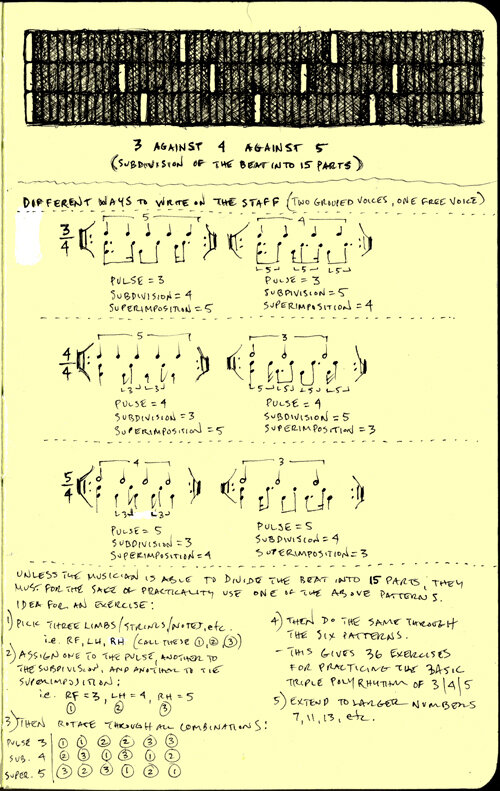

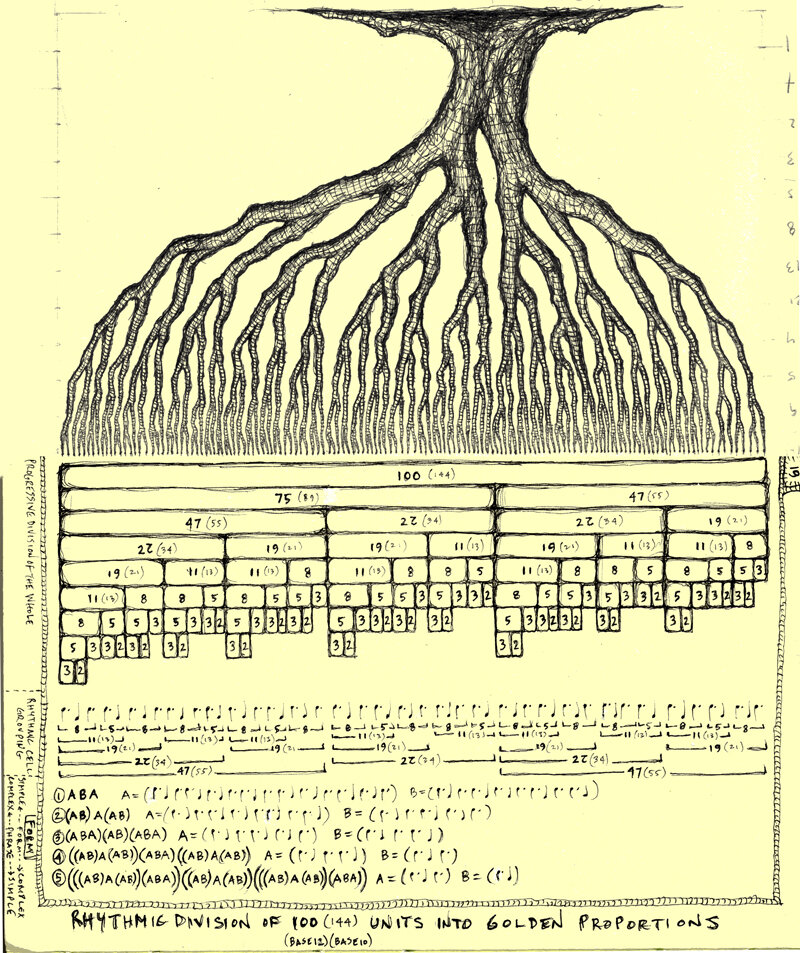

Musician’s Visual Reference (2014)

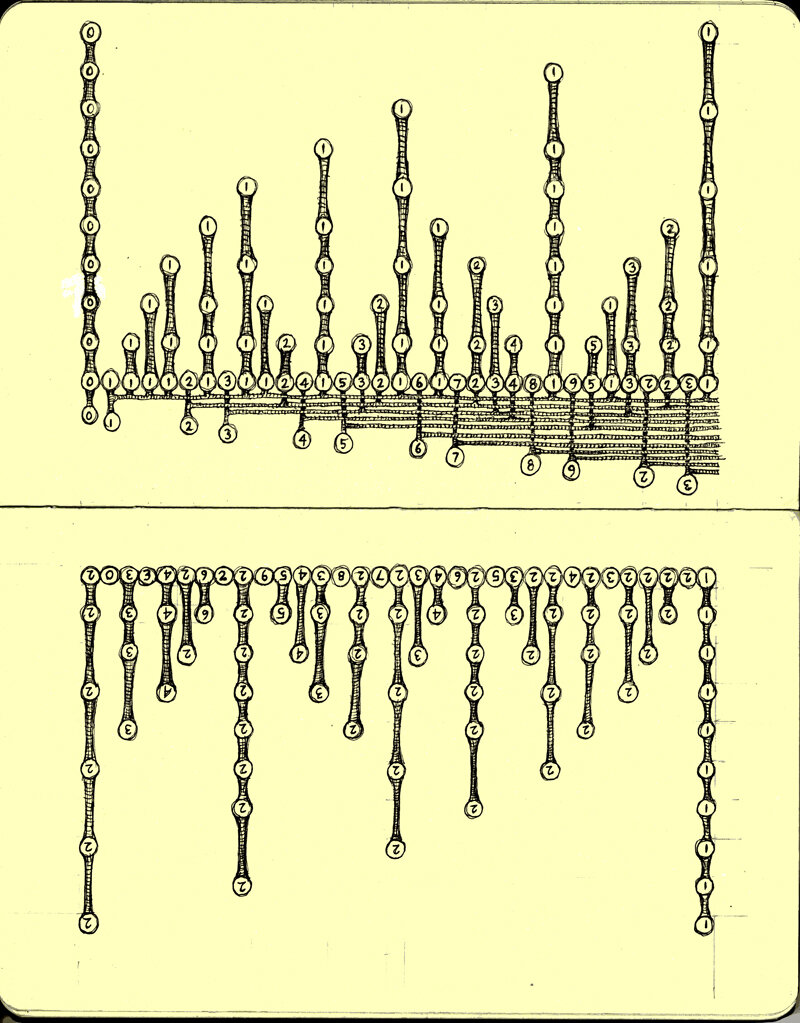

A collection of visualizations for organizing pitch and rhythmic information. Includes: 352 pitch collections, 1,211 rhythmic modes, 505 rhythmic cells, various pitch space maps.

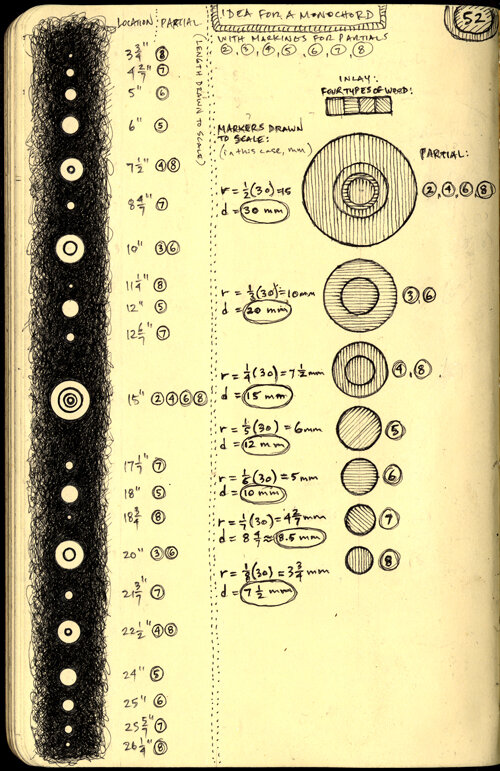

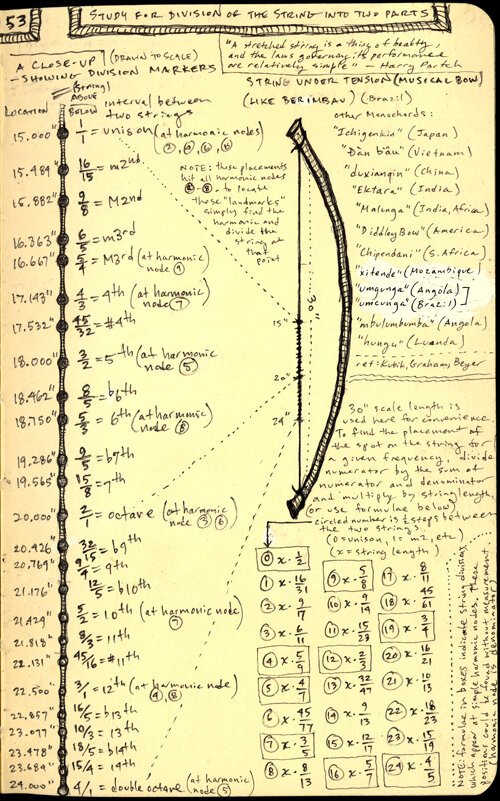

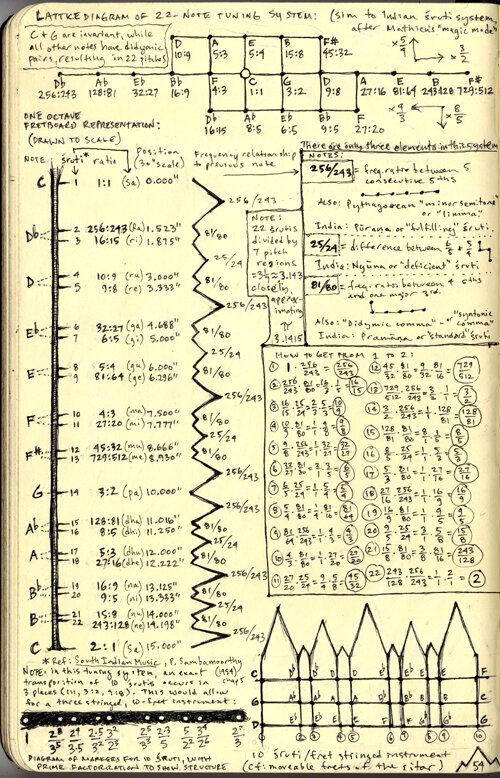

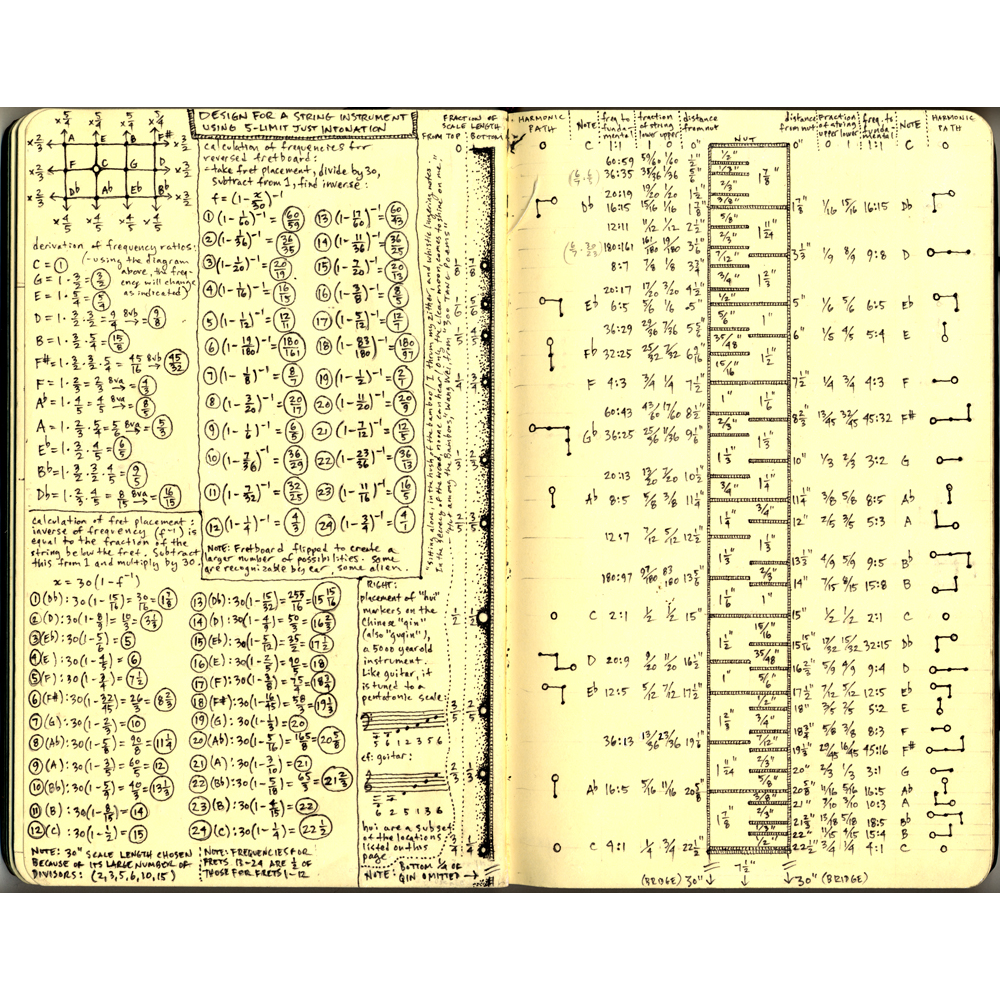

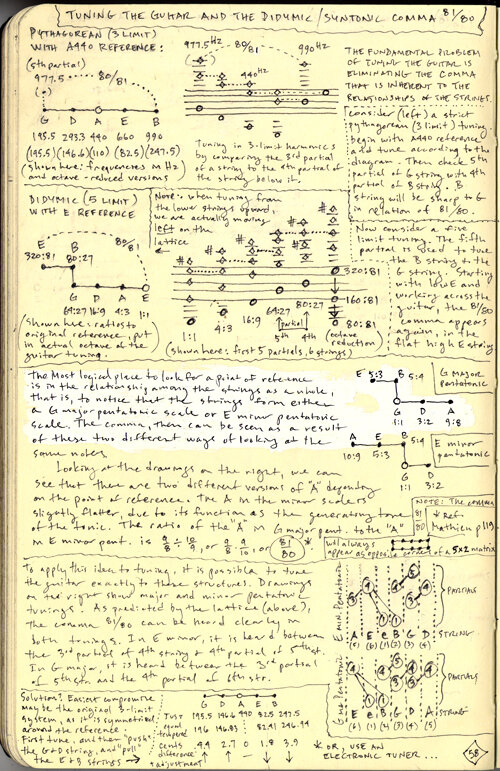

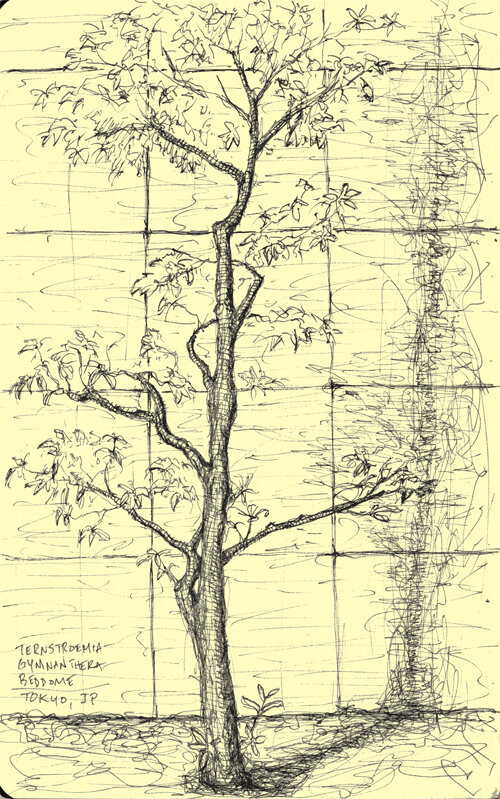

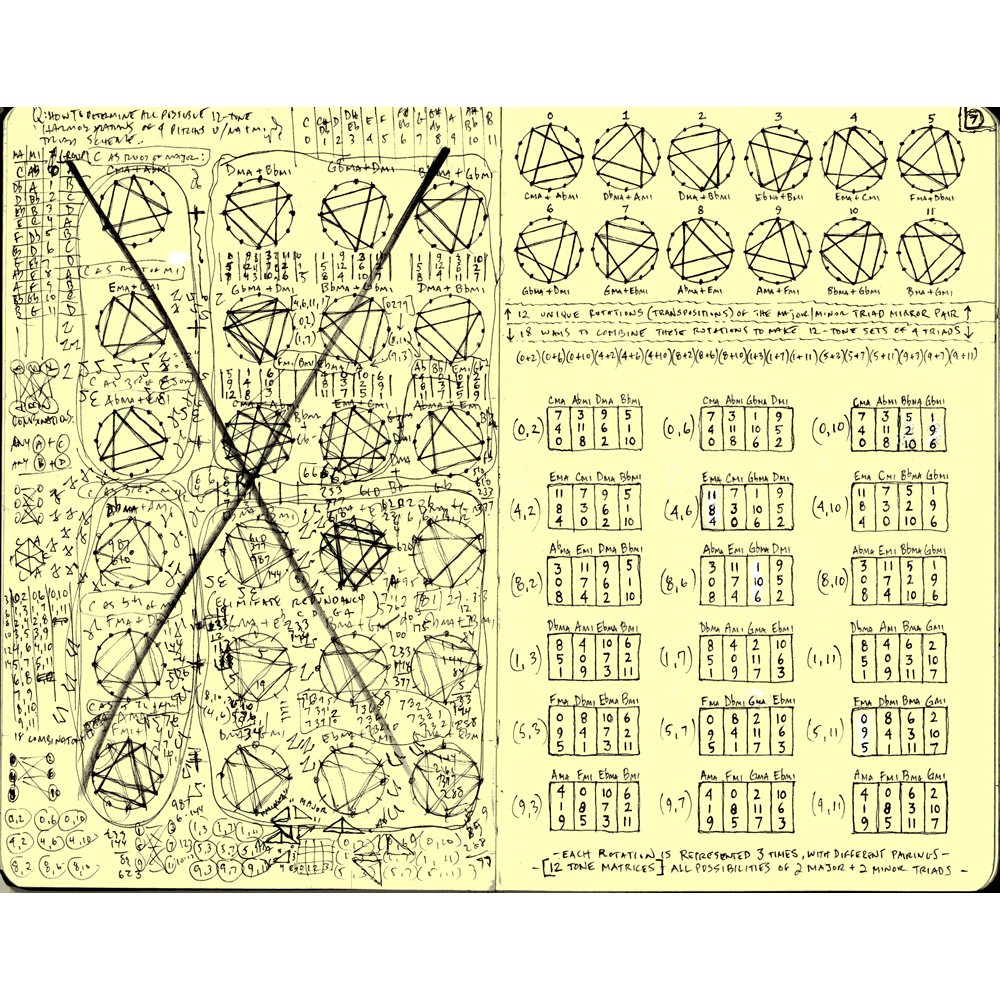

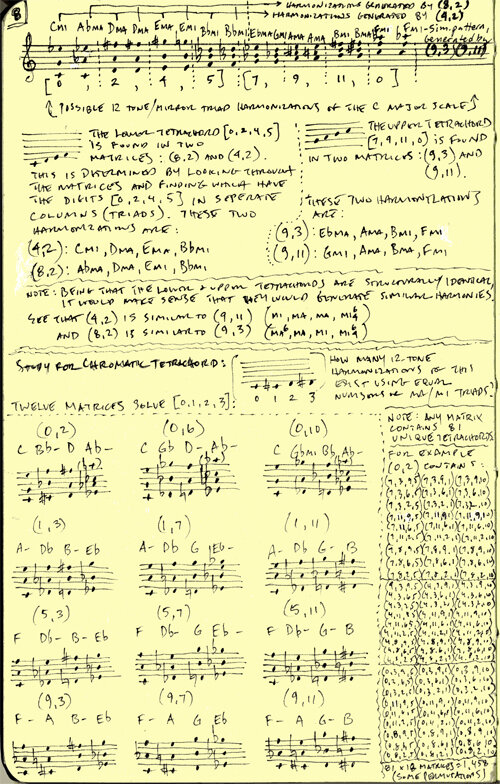

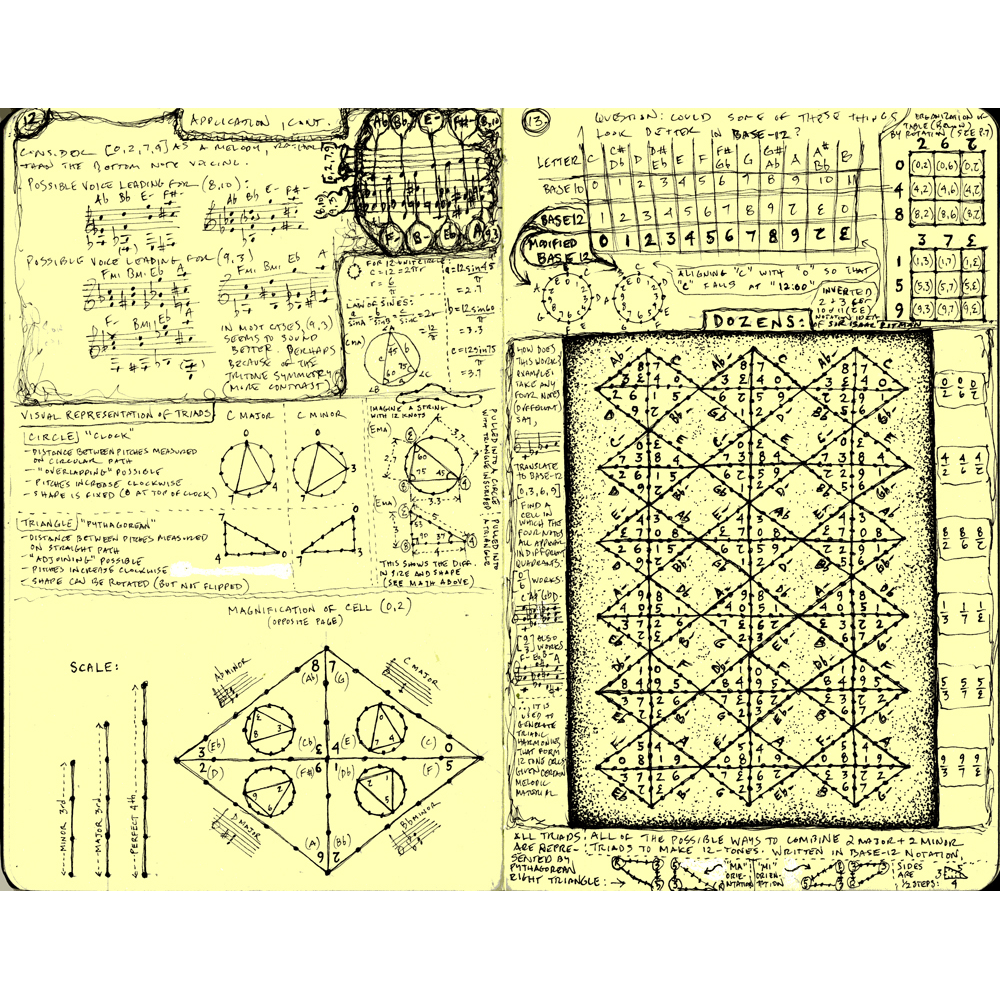

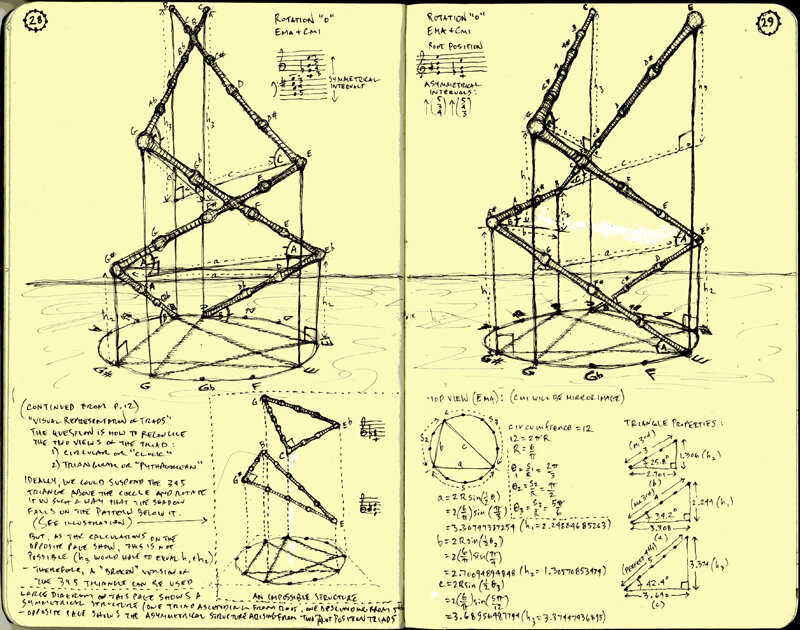

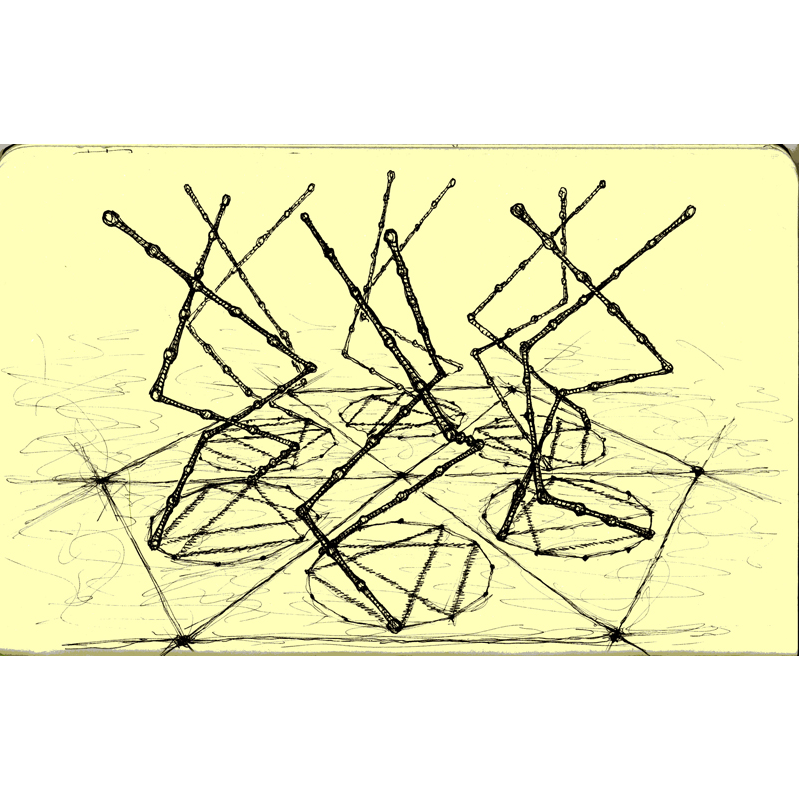

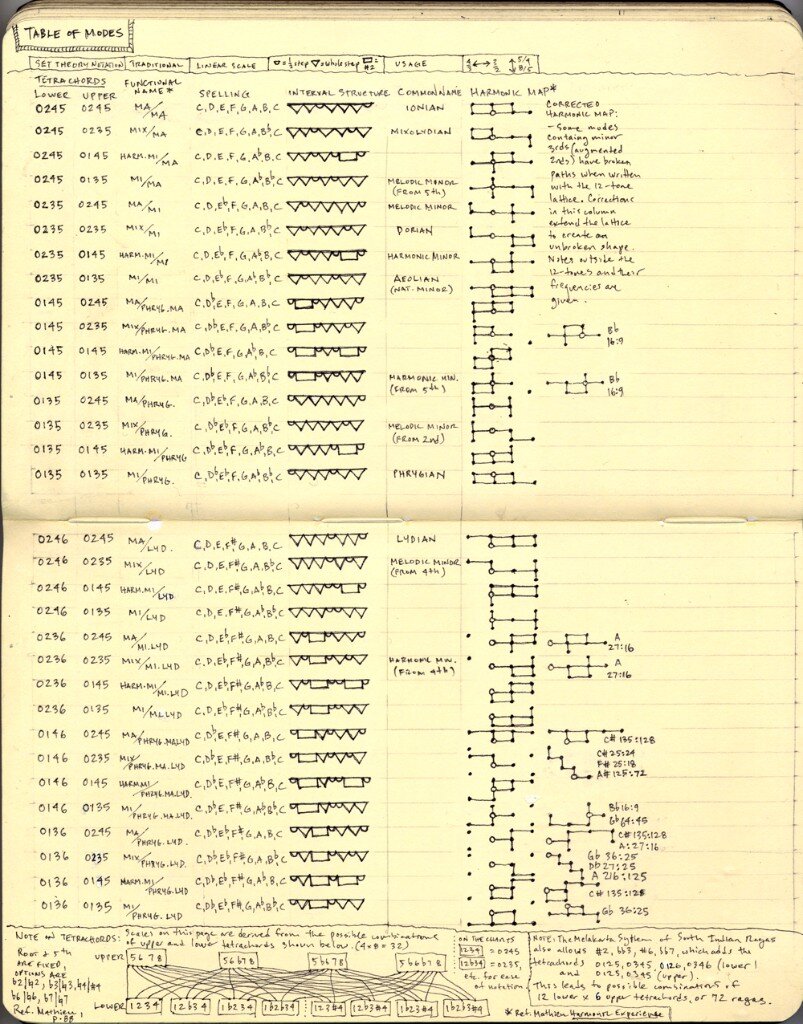

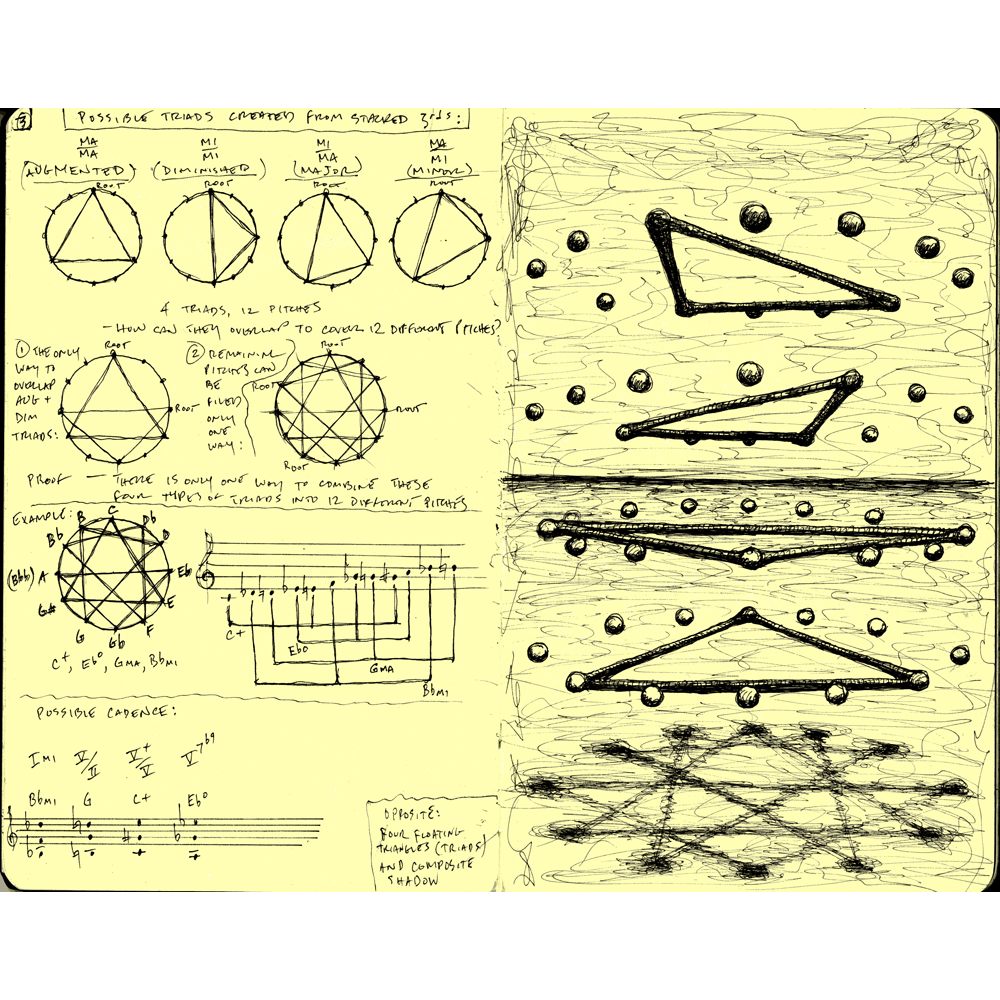

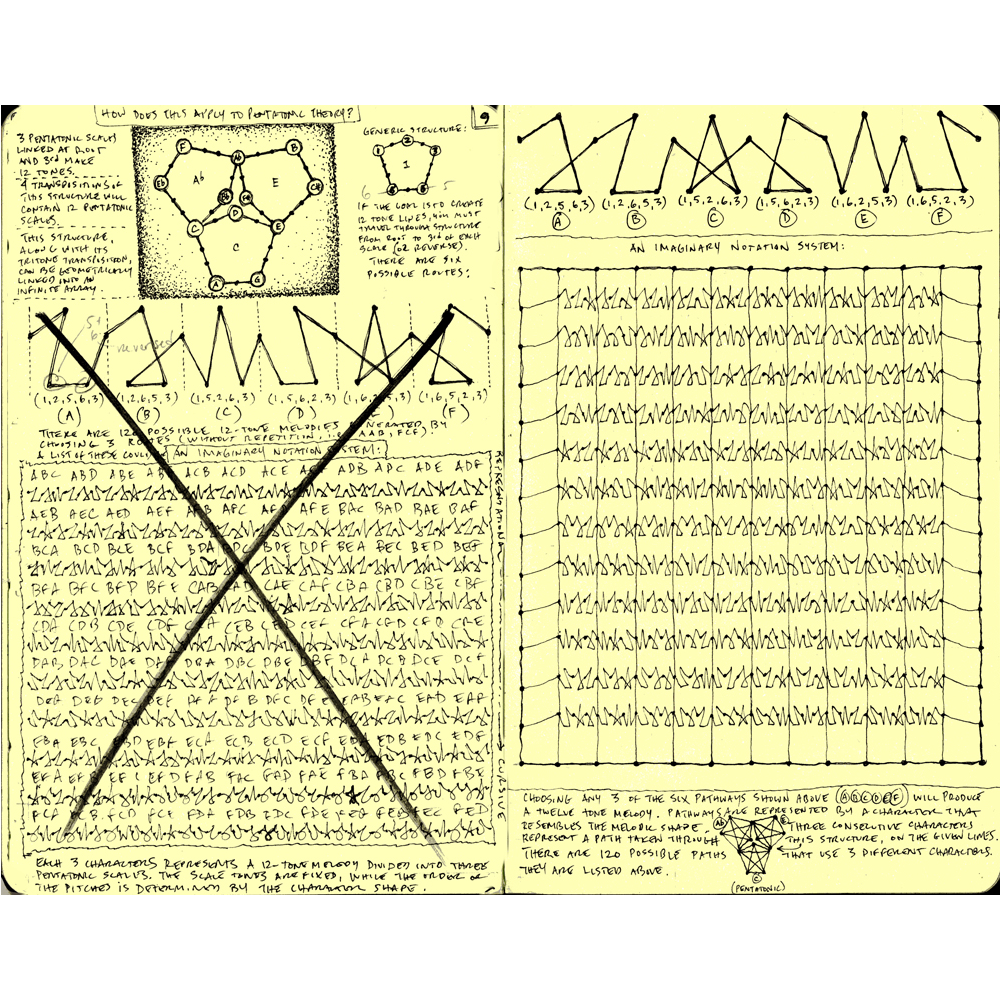

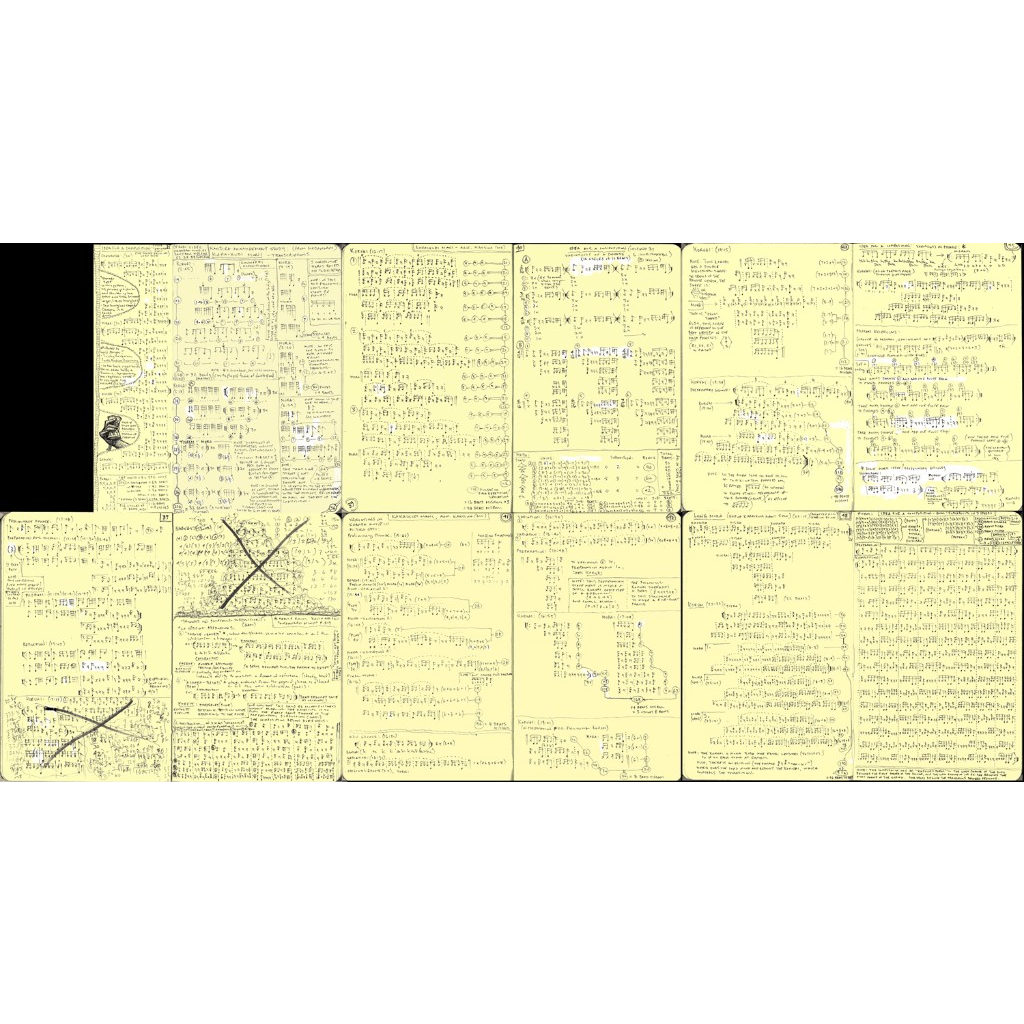

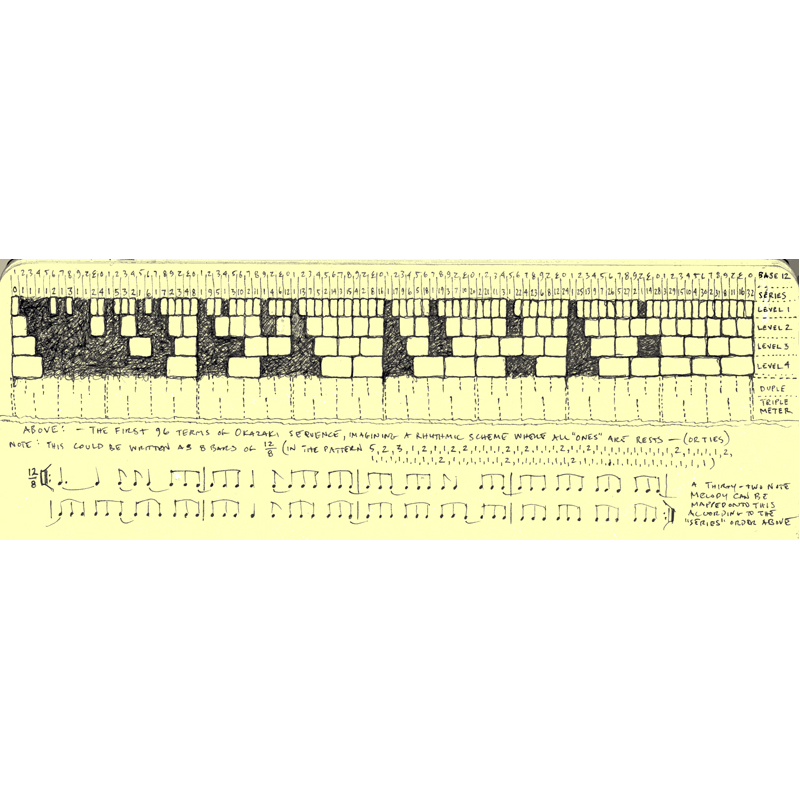

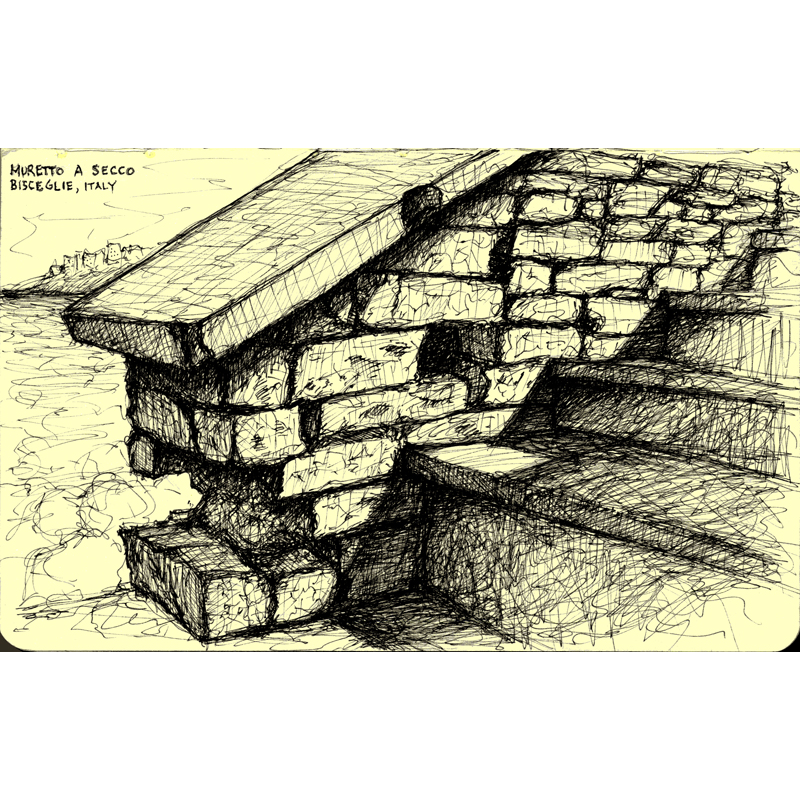

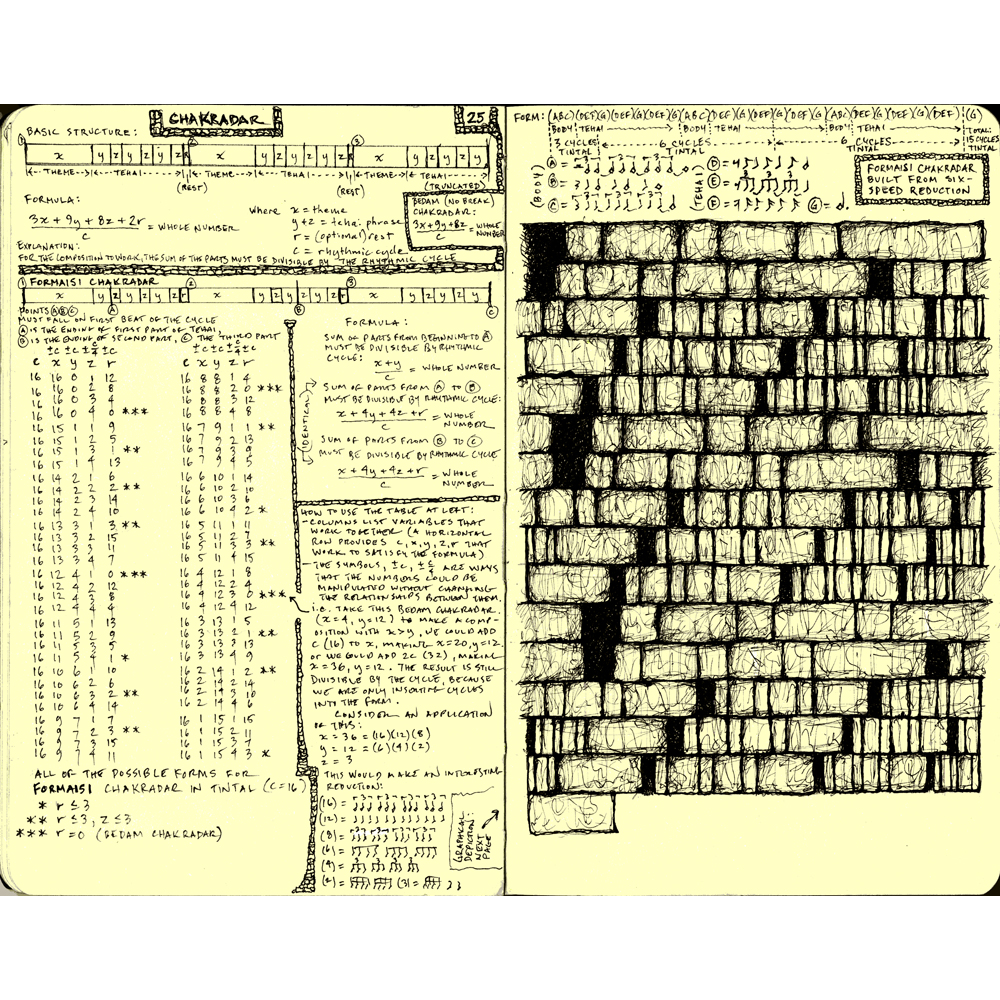

Notebook (2008)

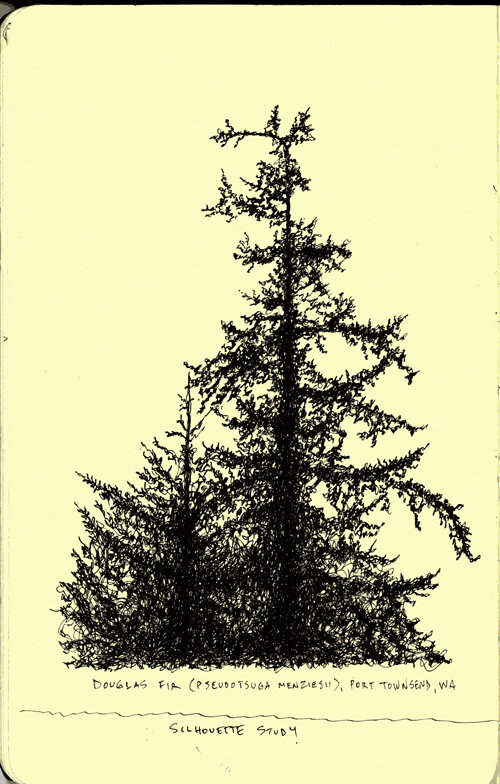

A notebook from 2008, with drawings and research for the album Generations:

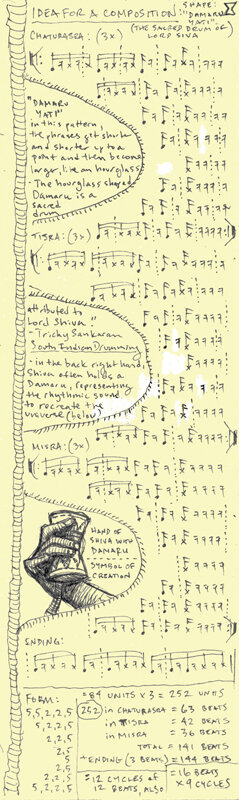

Four Pulse Study (2002)

A combinatorial study of Long and Short rhythmic cells within four beats, from 4 to 8 subdivisions of the beat (all possible patterns). Explanation is on the 3rd page.

Coltrane Studies (1998)

Some transcriptions of Coltrane solos

(made without slowing-down technology, so accuracy may not be up to modern standards)